Gov. Gavin Newsom faced a hefty bill for a foolhardy decision to dine at The French Laundry while Californians were locked away at home during the depths of the coronavirus.

But, 10 months later, he wasn’t sent to clean-up dishes by California voters to pay for it.

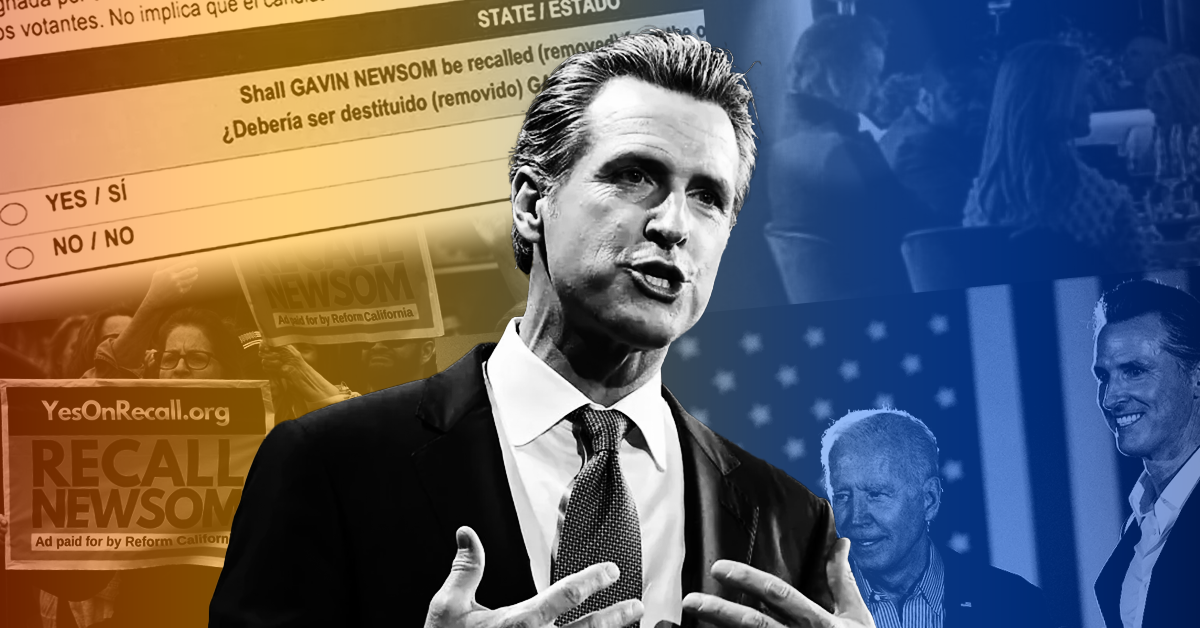

Late results Tuesday night indicated a resounding defeat of California’s second-ever gubernatorial recall, with 64.6 percent of voters rejecting the effort to oust Newsom.

Millions of ballots remain uncounted, but the result is likely cemented: Newsom isn’t going anywhere for the remainder of his term, set to expire Dec. 2022.

Tuesday night, one-by-one, contenders vying to oust Newsom conceded the race, noting the high bar set by the initial ballot question of whether to remove him from office.

Larry Elder, the conservative talk radio host, led the field of replacement candidates late Tuesday.

As his supporters, gathered in Costa Mesa, booed the news, Elder called on them to “be gracious in defeat.”

“We may have lost the battle,” Elder said in a late concession speech. “We are going to win the war.”

Former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer, the GOP’s runner-up in the foiled replacement contest, offered a similar outlook on the future with possibilities that he might not be done with statewide politics.

“I can tell you, as for what’s next for myself, I’m gonna take the time to talk not only to my family but to my supporters and figure out the best steps here in the coming weeks to continue to be a fighter, to continue to be serve our great state,” Faulconer said from San Diego. “California’s worth fighting for.”

“Tonight was round one, there’s more to come.”

In a victory speech, Newsom worked to cast the results of the recall ballot as an endorsement of his approach not only on the coronavirus pandemic, but the entirety of his three-year-old agenda.

“I want to focus on what we said yes to as a state,” he said from Sacramento. “We said yes to science. We said yes to vaccines. We said yes to ending this pandemic. We said yes to all those things that we hold dear as Californians and I would argue as Americans. Economic justice, social justice, racial justice, environmental justice are the values where California has made so much progress — all of those things were on the ballot this evening.”

He also doubled-down on a tried-and-true talking point by assailing “Trumpism” and its impact on the state’s election.

Shortly after he gave his concession speech and left California’s Democratic Party headquarters, Newsom tweeted out “Now, let’s get back to work.”

Key takeaways

How did California get through its second-ever recall election with Gov. Gavin Newsom victorious?

Beyond election mechanics – such as boosted absentee voting through all-mail balloting and Newsom’s cartoonish, $50 million campaign war chest – here are three of the key takeaways in the tussle for his job.

A Cacophony of California Concerns

The recall was nothing if long on issues and lines of attack for candidates hoping to succeed Newsom in the event of a recall.

Soaring cost of living from San Ysidro to Eureka compounded by lack of affordable housing for the middle class, a drastic increase in homelessness on the streets of virtually every California community, a continued rise in petty crimes and an historic surge in violent crime, and stagnant economic reopening due to boosted unemployment are just a sampling of the substantive fault lines utilized during the 90-day sprint.

That’s without seasonal issues like public safety power shutoffs and the state’s wildfire season.

In all, the cornucopia of issues forced GOP contenders to square a difficult rhetorical tightrope: that Newsom’s management of California was either driven by incompetence or deliberate intent.

In only a few cases would attacks center on the overlap, or intentional incompetence, like Newsom’s misrepresentation of wildfire prevention statistics to establish a veneer of addressing the problem.

But issue overload, as beneficial and difficult to manage, wasn’t the sole issue.

Politics, like comedy, is also about timing.

And renewed interest in the coronavirus – courtesy of the Delta variant – began to shift voters’ views in Newsom’s direction, too, especially as it collided with California’s back-to-school season and employers’ rejiggering of workflow in-person just as ballots would be sent to voters.

The Elder Effect

Newsom and his political team spent the early goings of the nearly-certified removal procedure by attempting to brand it “The Republican Recall.”

The branding cast the gambit an conspiratorial concoction of GOP design to usurp democracy, rather than the venting of pandemic-era political rage that united California’s Republicans with an outsized number of independents and Democrats, if only for a moment.

With limited exceptions, early polling gave little credence to the messaging strategy.

That is, until Larry Elder stepped into the frame.

Elder, a charismatic messenger with a large audience in the nation’s second-largest media market, wasted no time vaulting himself to the top of the polls with a no-nonsense assault on Newsom’s record.

But his his lengthy tenure on radio provided a potpourri of hot takes and sound bites that would eventually come to serve as masterful wedge issues littered in the pages of The Los Angeles Times, which ultimately trickled down to be regurgitated across the Golden State media landscape.

Prior to Elder’s entrance, Newsom’s political team struggled endlessly to tag vying contenders like John Cox and Kevin Faulconer with former President Donald Trump, to little avail.

One Newsom consultant seemingly spent every waking hour for months responding to virtually any tweet mentioning the former San Diego Mayor with photos of him flanking Trump in the Oval Office.

Elder, however, was quickly branded the “Black face of white supremacy” whose perceived philosophical proximity to Trump was anathema to the deeply-blue state.

The attacks aided in elevating Elder and serving as a badly-needed catalyst to turn out otherwise disaffected Democrats.

For Elder, meanwhile, he’s risen to a unique position, should he be willing to accept it: improbable leader of a political party that’s been in desperate search of a statewide comeback since 2006.

Speaking to KMJ earlier on Tuesday, Elder acknowledged as much.

“I have now become a political force here in California in general and particularly within the California Republican Party,” he said. “And I’m not going to leave the stage.”

The lingering question: Elder may occupy the stage, but can be bring back a sizable enough audience to win at the ballot box?

Antonio the Alternative

Suffice it to say, Tuesday night may have very well ended differently but for one tweak.

Unlike the 2003 rendition of the state’s recall, wherein Lt. Gov. Cruz Bustamante jumped into the replacement election, no major Democratic politico stepped up to the plate and opted to serve as an alternative to Newsom.

As elections officials processed signatures in mid-2021, most Democrats were sticking by their man in the Horseshoe.

That didn’t stop pundits from musing about the possibility that Newsom’s 2018 primary foe, former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, might enter the fray.

Villaraigosa, a teacher union organizer-turned-reformer who regularly locked horns with his former ilk, ran the state’s largest city that – years after he left City Hall – is plagued with many of the problems replacement contenders laid at Newsom’s feet.

But the former Mayor and Assembly Speaker didn’t step up and offer a Californians a second chance to embrace a Democrat-led, moderate vision for the state, even if it came at the expense of a Bay Area Democrat in the big chair.

It’s unclear what kept Villaraigosa away from a renewed challenge to Newsom – condemnation and scorn from fellow Democrats (earned by Bustamante in 2003) or promises of a future opportunity down the line – but the window to serve as the contrast is undoubtedly closed.

Though Newsom will be up for reelection to a four-year term in 2022, an intra-party squabble following an outsized recall victory will leave Democrats firmly in Newsom’s corner moving forward.

What’s next?

Newsom’s message following victory was pretty succinct: time to get back to work.

How emboldened he and legislative Democrats feel is still to-be-seen, but there is renewed hope that a special session of the California State Legislature – which adjourned for the year last Friday – will be convened to tackle a key issue.

That issue? Vaccine mandates.

Legislators bandied draft language of vaccine mandate legislation in the final days of session, only to see its author withdraw it due to obvious inopportune political timing and promising to return it in 2022.

But with Newsom secure in his post, continued drumbeating about the peak of the Delta variant, and a sizable unvaccinated population, a return to Sacramento to tackle the mandate may be in the cards.

As for what comes when the legislature reconvenes in 2022, it remains to be seen where Newsom goes from here.

But it’s safe to assume it will likely resemble the trajectory of the past three years, shy of one ill-fated trip to a Michelin-starred Napa eatery.