Dr. Shirley Weber, California’s top elections official, has quickly become “the woman to sue” if you’re on the recall ballot.

Weber, who stared down a legal challenge waged by the man who appointed her to the post – Gov. Gavin Newsom – and won, is now facing new legal challenges related to ballot designations and ballot access on the Sept. 14 recall.

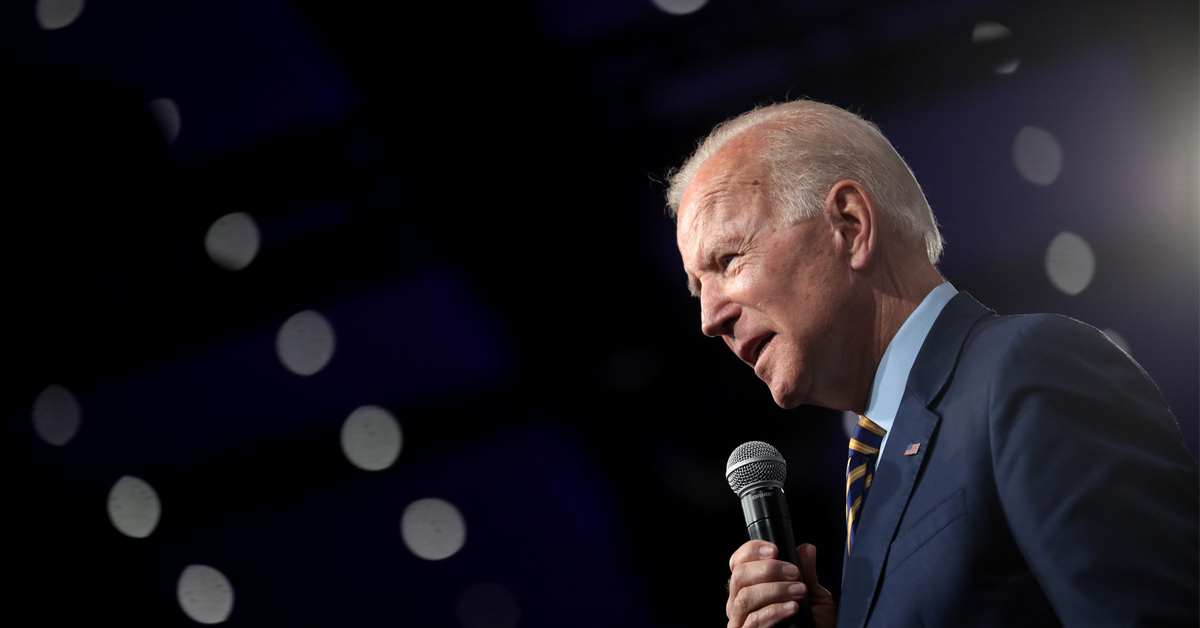

Weber defeated a challenge from Newsom over flubbed paperwork which would have guaranteed Newsom’s political party affiliation appeared on the recall ballot.

At the center of the battle was Senate Bill 151 – signed into law by Newsom on Oct. 8, 2019 – which greatly changed elements of the recall process for state elected officials.

The law enabled partisan public officials subject to a recall election the ability to display their party preference on the recall ballot. While approved in 2019, it wouldn’t come into effect until Jan. 1, 2020.

The law has a unique hitch: the to-be-recalled elected official must indicate whether to display his or her party affiliation on the recall ballot when they file their answer to the recall effort.

Newsom’s political team failed to indicate that the Governor wanted his party affiliation displayed when they filed their answer in early 2020.

In a ruling, a Sacramento County judge said “Governor Newsom argues that unique circumstances attending his untimely party designation support an order excusing the noncompliance. The Court is not persuaded.”

Monday, two potential legal challenges to decisions made by Weber have emerged.

The first, lingering from the weekend, is Los Angeles radio host Larry Elder’s ballot access.

Elder, whose candidacy is in question after Weber’s office stated he filed incomplete tax returns – a newly-crafted California requirement for ballot access in the post-Trump era – announced he would be suing Weber and her office over the decision.

“The Secretary of State is either saying that we did not redact sufficient info on my returns, or we redacted info that should not have been redacted,” Elder said in a tweeted statement. “The Secretary of State could have made the supposedly required redaction(s), but elected not to. We’re trying to ascertain the details.

“Regardless, income tax returns are required under the election code to ensure ‘that its voters make informed, educated choices in the voting booth.’ The redactions required on tax returns include items such as social security number, home address, telephone number, etc.,” Elder’s statement continued.

“Should they not be redacted inadvertently, it would be an error that does not arise to a disqualifying factor.”

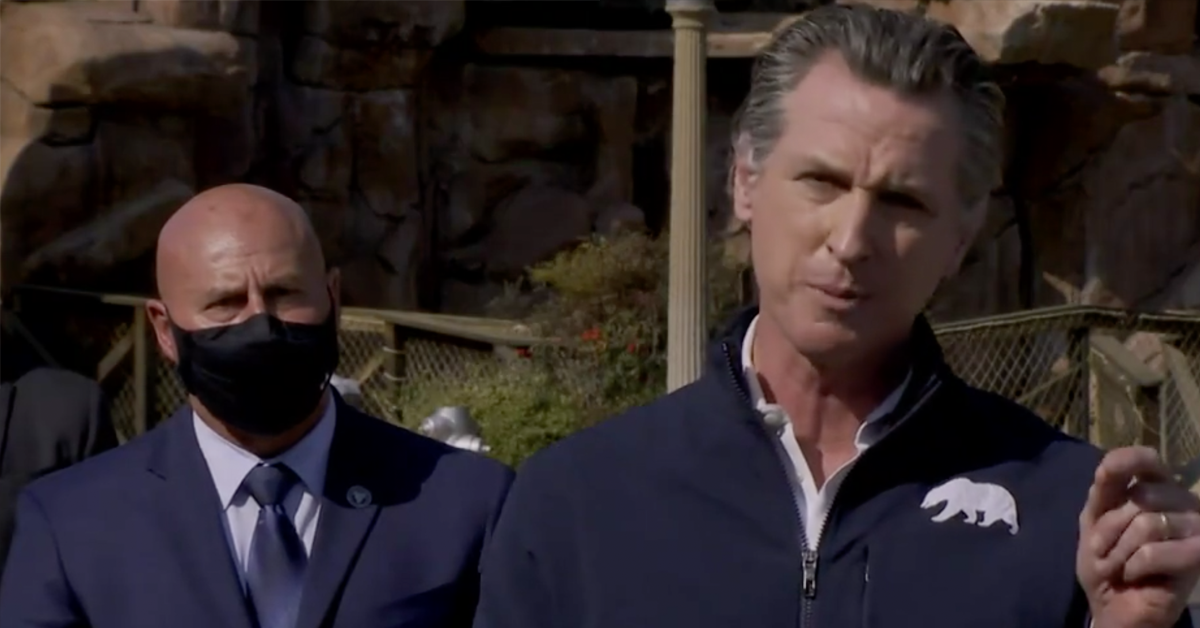

Meanwhile, former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer is joining the legal fray with his own suit.

The subject? The three-word ballot designation that will appear under his name.

When filing to run, Faulconer sought to have the phrase “Retired San Diego Mayor” as his ballot designation.

Under California law, the geographic location of “San Diego” counts as a single word rather than two.

Weber rejected the designation for use of the word “retired.”

“It defies common sense that Kevin Faulconer wouldn’t be allowed to use ‘retired San Diego Mayor’ as his ballot designation, where he was elected and re-elected, leaving office only at the end of last year,” Faulconer spokesman John Burke said in a statement. “This is not fair to voters who should be given accurate information as to who the candidates for this recall actually are. Our campaign is suing the Secretary of State to ensure that this is rectified.”

California election law defines the standard for ballot designations as “the principal professions, vocations, or occupations of the candidate during the calendar year immediately preceding the filing of nomination documents.”

While the word “retired” is allowed as a prefix, the elections code is silent on its definition.

The only candidate in recent years to stumble across a similar issue with ballot designations was former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, who battled with Newsom in the 2018 California Primary for the Governor’s seat.

Villaraigosa, who was five years removed from the Mayor’s office, used the ballot designation “Public Policy Advisor” due to the “one calendar year” rule laid out in California election law.

This story will be updated.