As California drags deeper into extreme drought, could the answer to the San Joaquin Valley and Southern California’s water woes be found via an oft-castigated bait fish on the Endangered Species list?

That’s the hope for one Valley congressional wannabe – former Fresno City Councilman Chris Mathys – who announced his intention to petition the Federal government to repeal the endangered species designation for the delta smelt in hopes of unlocking water flows south of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

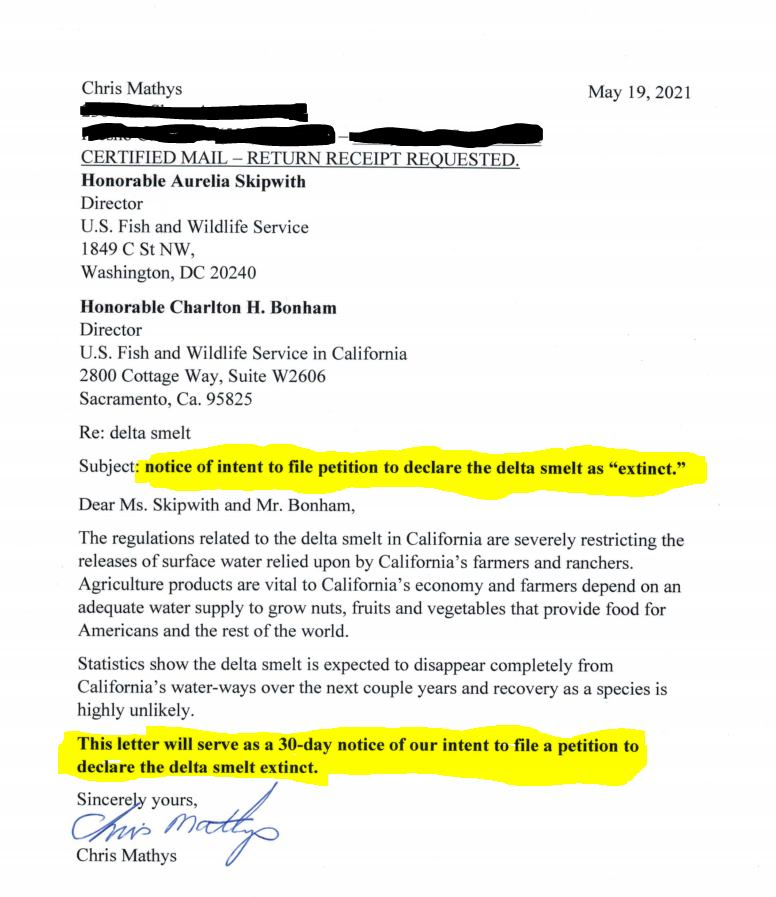

Wednesday, Mathys sent a letter addressed to officials of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announcing his intention to petition the department to “declare the delta smelt extinct.”

Misfires and hurdles, galore

The effort faced its first hiccup out of the gate: Mathys’ letter misidentifies the Federal agency leaders tasked with managing fish and wildlife species.

The letter was addressed to Aurelia Skipwith and Charlton “Chuck” Bonham of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Skipwith, a Trump administration appointee and the first-ever Black director of the agency, is no longer in Federal service following President Joe Biden’s inauguration on Jan. 20.

Meanwhile, Bonham is the director of California’s Fish and Wildlife Service and has no authority over the Federal Endangered Species Act.

But the push by Mathys opens the door to a much larger obstacle: the infamous “God Squad.”

Under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, there is one route to exempting an already endangered species from environmental protection laws: a determination by the Endangered Species Committee.

The committee, known informally as the “God Squad” is comprised of the Secretary of Agriculture, Secretary of the Army, Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors, Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, Secretary of the Interior, Administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and one individual from the affected State, as determined by the Secretary of the Interior and appointed by the President.

The God Squad is convened upon application of either a Federal agency, the Governor of the affected state (in this case, Gov. Gavin Newsom), or – in particular circumstances – a permit or license applicant.

Since the inception of the God Squad, which was crafted as part of a 1978 set of amendments to the Endangered Species Act, only two species have been deemed exempt from the law: the whooping crane and the northern spotted owl (the latter of which was overturned by a California Federal appeals judge who found White House officials had attempted to influence the outcome).

‘God Squad’ raised before

The prospect of having the God Squad intervene in the regulation of delta smelt populations on the Delta and its connected waterways has been flirted with in the past.

In 2016, as Congress debated government funding, southern California Rep. Ken Calvert (R–Corona) – then the chairman of the House Appropriations subcommittee tasked with overseeing spending for the Department of the Interior – probed the then-director of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Dan Ashe on the subject of convening the God Squad to make a determination on delta smelt.

“I do think the Endangered Species Committee — none of us likes to think about being at this place, but it’s in the law for a reason,” Ashe told Calvert during the March 2016 hearing.

“It’s a reasonable question for you to ask, have we arrived at a place where we should convene the Endangered Species Committee. It’s the only forum to balance benefits to species against economic and other forces.”

At the time, Ashe noted that the agency’s species recovery efforts were “not helping the delta smelt” adding that it “turn a blind eye to a species that is about to go extinct.”

Calvert turned the dejected view of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as an opportunity to change approach related to fish species in the delta.

“El Niño has proven that the problem is not quantity of water, but the regulation of water,” Calvert said, kicking off the 2016 hearing. “And so much of the regulation is dictated by the Fish and Wildlife Service under the mandates of the Endangered Species Act, with wide latitude afforded scientific uncertainty, and a save-at-any-cost policy that borders on dogma. Enough is enough.”

There’s always a bigger fish

Yet, much has changed since 2016.

California water experts, speaking to The Sun on background, cast off the God Squad option as having an infinitesimal chance of being convened to deliberate on the delta smelt question, let alone deemed exempt from Endangered Species regulations.

And should that rare occurrence come to pass?

The possible outcomes range from preservation of the status quo on pumping water to more drastic environmental restrictions on water flows, they argue.

They note that the 2019 Federal biological opinions guiding the restrictions of water exports south from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta also cover impacts to other species of fish covered by the Endangered Species Act, including Sacramento River winter-run chinook salmon, Central Valley spring-run Chinook salmon, and California Central Valley steelhead.

Other experts speaking to The Sun noted that the greater restriction on flows currently isn’t arising from delta smelt protections, but from protections for salmon species (such as those previously noted) and the Shasta Dam Temperature Control Plan.

Meanwhile, other hypotheticals have their own impacts, such as a difference of opinion between the Federal government and State of California water regulators, due to California’s companion version of the Endangered Species Act.

An exemption issued by the Federal “God Squad” could lead to a split of authority over pumping water – relative to impacts on delta smelt – potentially resulting in slightly heavier pumping operations for Central Valley Project water users at the expense of State Water Project users.

Attainable goals on the horizon, rep says

For the man Mathys hopes to oust, Rep. David Valadao (R–Hanford), better options to secure water supplies lie with extending key provisions from the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (WIIN) Act – a law spearheaded by House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy (R–Bakersfield) and Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D–Calif.) in the waning days of the Obama administration.

The law is set to expire at the end of this year.

By extending the law, as Valadao’s marquee bill (the RENEW WIIN Act) seeks to do, Federal officials can continue to fund water storage projects in the Golden State.

“First and foremost, it is the responsibility of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to make decisions on listing determinations and designations based on the best available science,” Valadao said in a statement to The Sun. “My bill, the RENEW WIIN Act, which is an extension of Subtitle J of the WIIN ACT, would ultimately provide more water storage to help mitigate the severity of droughts, providing more water for all users – including communities, farmers, and fish.”