As if California’s drought situation could get no worse, water agencies and poor communities in the southern San Joaquin Valley are confronting a new reality.

While they receive no water from the State Water Project, they’re being hit with rate hikes of up to 18 percent from last year by California water officials.

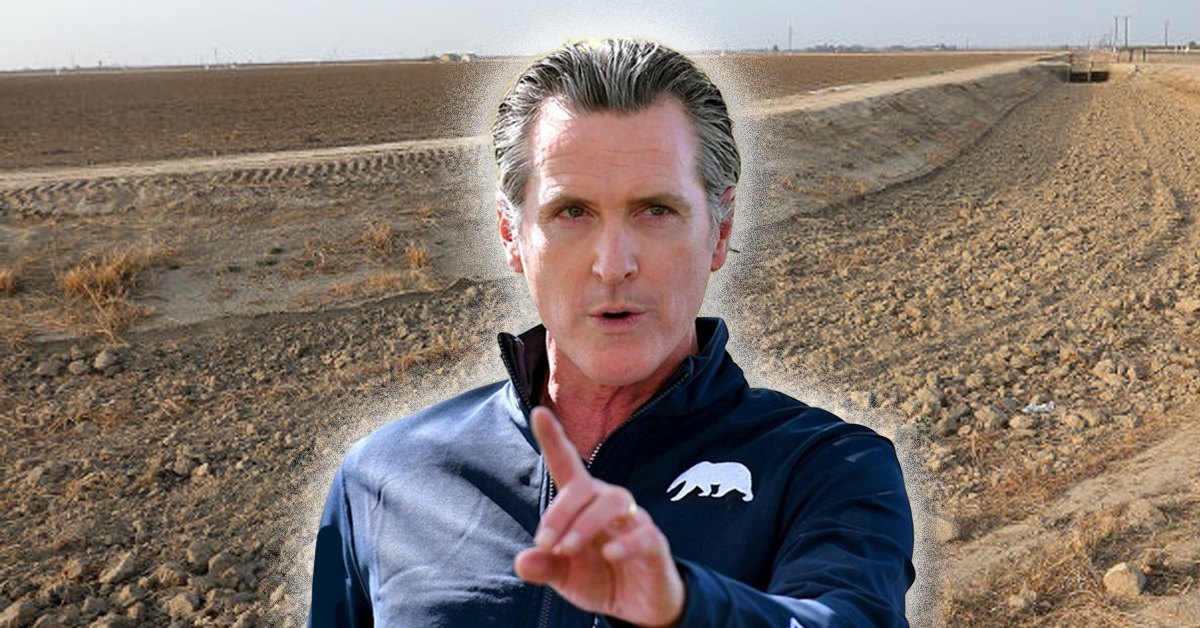

In a letter to Gov. Gavin Newsom, state water users in the old Tulare Lake bed – including water agencies that serve some of the state’s poorest communities – called for the Department of Water Resources to halt its planned hike on water rates.

“DWR has informed these Districts and the County, along with three other state water contractors who comprise DWR’s San Joaquin Valley region, that their water charges for 2022 will increase by $25 million over this year,” the letter reads.

“This is a 13% to 18% increase for these contractors in a single year.”

The letter was signed by Kings County, Tulare Lake Basin Water Storage District, Empire West Side Irrigation District, the City of Corcoran along with representatives from water providers in Kettleman City, Stratford, and Alpaugh.

The signatories argued that, if conditions persist into 2022, they will be paying an estimated $3,000 per acre foot of water they receive – if they receive any at all.

The state’s current water restrictions have “caused the fallowing of over fifty thousand acres of productive farm land in the Tulare Lake Basin this year,” the south Valley group argues.

Conditions are particularly dire among the three unincorporated towns in Kings and Tulare counties.

According to the agencies, Kettleman City and its 1,400 residents are set to run out of potable water from the State Water Project by December.

Kettleman, a popular stopover for Californians traversing Interstate 5 between Los Angeles and San Francisco, has a dizzying 10.5 percent unemployment rate with 32.5 percent of its residents living below the Federal poverty line.

For the poorest communities and the water agencies that keep neighboring fields productive and employing workers, the issue is one of fundamental fairness.

Regardless of how much water is sent to communities and farms on the State Water Project, the agencies and residents are expected to pay for 100 percent of the cost of delivery.

“On top of the crushing financial burden that will result if DWR’s proposal is not suspended, the signatory contractors also must pay for 100 percent of its state water entitlement even though they will receive no more than 5 percent,” the letter reads.

That arrangement isn’t the norm for water agencies that rely on the Federally-operated Central Valley Project for their water supplies.

After operations and maintenance costs, Federal water contractors only pay the water they receive.

Justin Mendes, regulatory chief for Tulare Lake Basin Water Storage District, said that the push for maintaining water rates extends far beyond haggling over the price of the most precious commodity.

“Water issues in California are often complex. This isn’t,” Mendes said in an interview with The Sun. “Increasing the cost of water while reducing or eliminating the supply is simply not sustainable. But far worse: it’s putting the communities of farmworkers on the brink of extinction with nowhere else to go.”