Kenny Washington, the man who broke the color barrier in the modern era of the NFL, is widely unknown, unlike his UCLA football teammate Jackie Robinson.

While the NFL had a handful of Black players in the league up until 1933, the league went through a 12-year period of segregation until Washington broke through following the end of World War II.

Washington signed with the LA Rams in 1946 at the age of 28, one year prior to Robinson breaking baseball’s color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

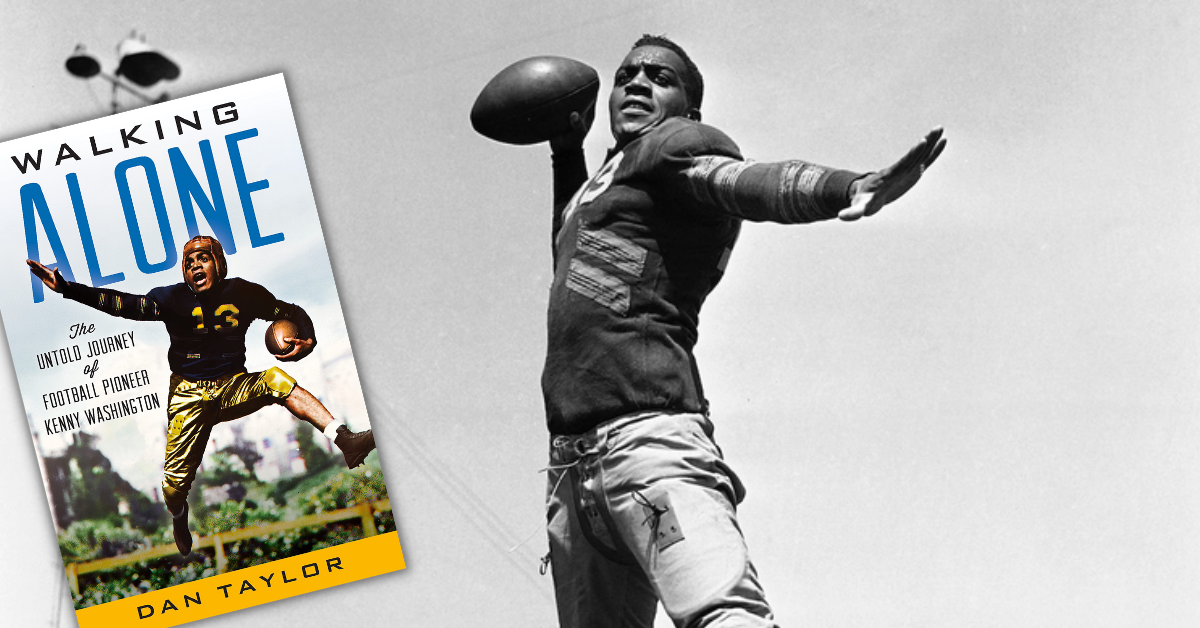

Former longtime ABC 30 sportscaster turned author Dan Taylor released his latest book on Wednesday – Walking Alone: The Untold Journey of Football Pioneer Kenny Washington.

The Sun’s Daniel Gligich spoke to Taylor about Washington and his latest book.

Daniel Gligich: What drew your interest to Kenny Washington to take on this project and write this book?

Dan Taylor: It came from a conversation with a great friend down in Los Angeles, and he was a UCLA guy. He taught at UCLA in the ’60s, and he was telling me that there were a couple of professors that he worked with who had been at UCLA in the late ’30s when Kenny Washington and Jackie Robinson were there, and that these professors continually said that Kenny Washington was the far better athlete. That he was the better football player, and he was the better baseball player. I had heard of Kenny Washington but really didn’t know a lot about him. And from that conversation I began doing a little digging and was just floored by the things I found out about him and what a remarkable athlete he was and what a tremendous place he has in history — both societal and also sports history. And I thought, ‘I’m really shocked that this story has never been told.’ That got me rolling up the sleeves and here we are.

DG: There are hardly any books out there about Kenny Washington. A quick search online just reveals a couple that have not gained much attention. Did you see this as an opportunity to fill a hole in sports history?

DT: I did the same thing. I initially thought, ‘Have I missed something here? Has this story been told and I missed it?’ Because I do read a lot. I couldn’t find anything, and I put my proposal together and sent it in to the editor that I work with at Roman & Littlefield, and she came right back and said, ‘Do you mean to tell me this story has never been told?’ And I said, ‘I can’t find any evidence that it has.’ We both agreed the people need to know about Kenny Washington, so we moved forward with it.

DG: When did you start working on the project and how long did it take?

DT: Maybe a year and a half. A good and bad part of it was that it was during the lockdown. Good because it certainly helped me in addition to my job at the time to give me something to focus on, and I thought from a mental health perspective that was great to get through a very difficult time. Challenging because so much was closed. So many people, for instance at UCLA, that I tried to get with to try to get access to things. A lot of people were working from home at that time and couldn’t get into the library to pull up stuff and check the video library and things of that nature, so that made it very very challenging. It was an interesting time, for sure.

DG: I’m assuming you formed a relationship with Kenny Washington’s family throughout working on this book. Can you share what your relationship has been like with them and their excitement for the book?

DT: He has a daughter and a couple of grandsons, one of whom who I spoke with and in fact exchanged emails with today. They were helpful to a point, and I say that not in a negative way. Karin Cohen is his daughter, and she was very upfront when we first spoke. And she acknowledged that she was adopted by Kenny and his wife June well after Kenny’s playing days were done. She said, ‘To me he was just daddy. I didn’t know he was this great athlete.’ She said, ‘One day I came home from school and Willie Mays is sitting at the kitchen table. I listened to he and my dad talk, and I thought, ‘My dad must have been somebody.” But Kenny died at a very young age of an incurable and extremely rare heart and lung disease. As Karin told me, ‘I didn’t get the stories. I just didn’t get the stories before he died.’ She was saying, ‘I can help you to a point, but’ — and his grandsons were the same way. Kenny had a son, Kenny Jr., who was born in ’41. He passed away a few years ago, and his two boys both played professional baseball, minor league baseball. They said, ‘We certainly know certain things, but we don’t have a great depth of knowledge of our grandfather.’ In fact one of them emailed me this morning that he had gotten the book and started to read it and said, ‘I’m learning so much about my grandfather that I never knew.’ So it’s challenging. There were some really interesting people through the process, and amazing stories. I found the daughters of Babe Horrell who was the coach of the ’39 UCLA Bruins, Jackie and Kenny’s coach. And one of the women was 93, the other 92. And they were great. Just had tremendous stories and great recall. One of them apologized and said she was in a bit of pain because she had fallen and fractured her elbow playing tennis, and I thought, ‘Boy you’re my idol. When I’m 93 I want to be playing tennis, incredible.’ And then I had found the daughter of Ned Mathews, who was the quarterback on the ’39 team. She was upfront, she said, ‘I really didn’t talk football with my dad, but my husband did.’ So she put him on the line, and the first thing he says is, ‘Now you’ve spoken to B, haven’t you?’ And I didn’t know who he was talking about. He said. ‘Ned’s wife.’ And I thought, ‘Wait a minute, Ned would be 103.’ He said, ‘Yeah, she’s 102.’ And I said, ‘Is she lucid?’ There’s certain times of the day, sometimes people that age you’re going to get them best if you get them early in the morning. And he goes, ‘Oh she’s great, give her a call now.’ This was in the evening, so I did and it went to voicemail. She called me back the next morning and she said, Oh I didn’t take you’re call because I wanted to double check some things in scrap books. In talking to this woman I never would’ve guessed that she was 102. She just sounded great. She apologizes, she said, ‘My voice might sound a little scratchy. I’ve been eating chocolate this morning.’ I thought, ‘No you’re my hero, I want to be eating chocolate at 102.’ It was difficult that way. Kenny’s son had passed. Woody Strode, who was his very close friend and teammate, he had passed. His son had passed. So it was really difficult finding people. There were a lot of questions I had that were never able to get answered simply because people are just not around. Still I felt I was really able to tell his story in the best way possible.

DG: Kenny Washington isn’t a household name like Jackie Robinson, yet the pair played football together for UCLA and endured similar struggles against racism. Major League Baseball honors Jackie Robinson, rightfully so, as a national hero, but the NFL does not do the same for Washington. Why do you think that is?

DT: I think in terms of the NFL, just playing Devil’s Advocate here, Kenny basically — we talk of him and he’s mentioned as the Jackie Robinson of the NFL. But in reality up through 1933 there were African Americans in the game. There were about half a dozen. When Joe Lillard was cut by the Chicago Cardinals, the league adopted this unofficial wink wink we’re not going to sign Black players policy. There had been an issue with Lillard and players from the South. The games just disintegrated into brawls. Players from the South taking out there feelings on Lillard and turning games into melees. So there were teams that just didn’t want to touch Black players because there were really good players coming out of the South, and there were other reasons of course. I think that the league has to look at that and say, ‘If we recognize Kenny we do a disservice to Paul Robeson and others who played in the late ’20s, early ’30s.’ That’s just my assumption looking at it. But still, there was a 12-year ban. Kenny endured a lot in his three years with the Rams. He took a lot of abuse, and I do think that the NFL should recognize him. I really do.

DG: A common point in Walking Alone is the immense popularity that followed Kenny Washington around, and the huge crowds that showed up to watch him play on the field. What made Kenny such a popular figure?

DT: Well I think his personality — No. 1, he was a very likable guy. But I think it was his skills. He could throw a football 100 yards. He was a tremendous running back. He had the speed to get around the edge and outrun defensive backs. He had the power to run off tackle. He was just a tremendous football talent when he played in the College All-America game against he Green Bay Packers. After the game there were Packers players who said, ‘If he came into our league he’d be the most exciting player in the league.’ Similarly when he was with the Hollywood Bears and they had an exhibition game with the Washington Redskins at that time, they had people with the Redskins who said the same thing. He would be the most electrifying, exciting player to come into the NFL. So I think his style of play was very appealing. He put UCLA football on the map. They had not been a very good program up until his arrival. The ’39 season was the first of, to this day, only two undefeated seasons in UCLA history. And professionally I think what he did with the Hollywood Bears really laid the foundation for pro football to enjoy success in Southern California. Pro football had not had much success on the West Coast. It had been exhibitions, independent teams that played traveling games. And in many cases it was fly by night promoters and bad owners who didn’t pay their bills. When Paul Schissler started the Pacific Coast Football League for the 1940 fall. Kenny, his popularity just shifted over from UCLA and he packed them in at Gilmore Stadium. It was pretty routine for the Hollywood Bears to have sellout or close to capacity crowds. And I think that really did lay the foundation for the Rams to be able to come in in ’46 and have success.

DG: Was there something that surprised you that you discovered in your research?

DT: Yeah, the baseball side of it, because I had certainly heard of Kenny Washington. You go to UCLA games and his number’s retired. You hear him mentioned as the first African American in the modern era of the NFL. But I had no idea of the baseball side of him and that he was an even better baseball player than a football player. When Jackie Robinson signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers he was trying to convince Branch Rickey to also sign Kenny Washington. And people felt that he was far better as a baseball player than Jackie Robinson and that there were scouts who felt that if he could have come into professional baseball out of UCLA he may have ended up being one of the great power hitters of all time. I was stunned by that. I didn’t know anything about his motion picture career, the 10 movies that he made, or the brief foray at UCLA into boxing that led some of the biggest names in boxing to try and convince him to become a professional heavyweight prize fighter. It’s juts remarkable. I had no idea about any of that. It was fascinating.

DG: A tragic part early on in Walking Alone is that Kenny’s uncle passed away on Highway 99 near Tulare. It’s a local connection for the Central Valley, albeit an awful one. Are there other local connections that Fresno and the Central Valley as a whole have to Washington that you discovered?

DT: In 1944 he played two games at Ratcliffe Stadium. When the war broke out the Pacific Coast Football League went on hiatus. A great many of their players and even coaches went into the military. And a local entrepreneur in 1944 tried to start a new professional football league, the APFL, the American Professional Football League. Kenny joined that league with the San Francisco Clippers. Kenny wanted to serve, but he had a young family so he was very low on the draft list, so to serve he ended up joining the LA Police Department and worked in the LAPD for 2.5 years. When the APFL started he resigned his position and signed with the San Francisco Clippers. They had a lot of weather issues in San Francisco. They had rains that really kept their gates down, even forced them to postpone some games. So they took a couple of games on the road and brought them down here to Fresno. Jack Mulkey who was an All-American end at Fresno State was part of the San Francisco Clippers. He was Washington’s favorite receiving target, and Mulkey told people that Kenny was the greatest player he had every seen. They came into Fresno a couple of times and played games at Ratcliffe Stadium. I think the first one they deemed as a huge flop because they played a night game and fog rolled in, so the crowd was kind of held down. The movie that he starred in While Thousands Cheer in 1940, they starred a lot of scenes, chase scenes and stuff, on roads here in the Central Valley. I don’t know specifics, but I did come across both trades and in newspapers articles that indicated that there were a number of chase scenes that they shot up around here.

DG: What do you hope people take away from Walking Alone and learn from the Kenny Washington story?

DT: I would hope people would come away from it feeling the way I think I and others feel of reading of other great athletes from the ’30s and ’40s. I grew up loving to read, so I grew up knowing about people like Sammy Baugh and people like that, and not Kenny Washington. I think it’s wrong, and I hope that this fills that void and that people now will include the name Kenny Washington when they think about the greatest players in professional football history.

DG: Lastly, I’d like to ask you about an experience with your previous book, Lights, Camera, Fastball: How the Hollywood Stars Changed Baseball. You had the opportunity to visit the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, last month and present your book. How special of an experience was that for you?

DT: It was a very special experience. I have a great regard for the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. The people there are wonderful. To be invited back was just a very special opportunity, and they were wonderful getting to meet and spend some time with Josh Rawitch, the new president of the Hall of Fame, was terrific. It was a very moving opportunity to be part of the offering there at the Baseball Hall of Fame. We had a great time. It’s a wonderful place in America, and just to be part of what they did was a tremendous honor.