With California’s high-speed rail reemerging as a financial hot potato, it appears that the sharpening knives of California Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D–Paramount) will remain far away from the woebegone project.

Wednesday, ahead of a final budget vote, state lawmakers and Gov. Gavin Newsom agreed to a plan to fund the final phase of construction toward for the Valley-centric bullet train and set up an inspector general to audit the major project to help authorize billions of dollars in funding for the rail plans throughout the state.

The agreement puts an end to the deadlock in Sacramento that has lasted for over a year regarding how to spend the remaining portion of $4.2 billion in bond funds for high-speed rail, which was approved by California voters in 2008.

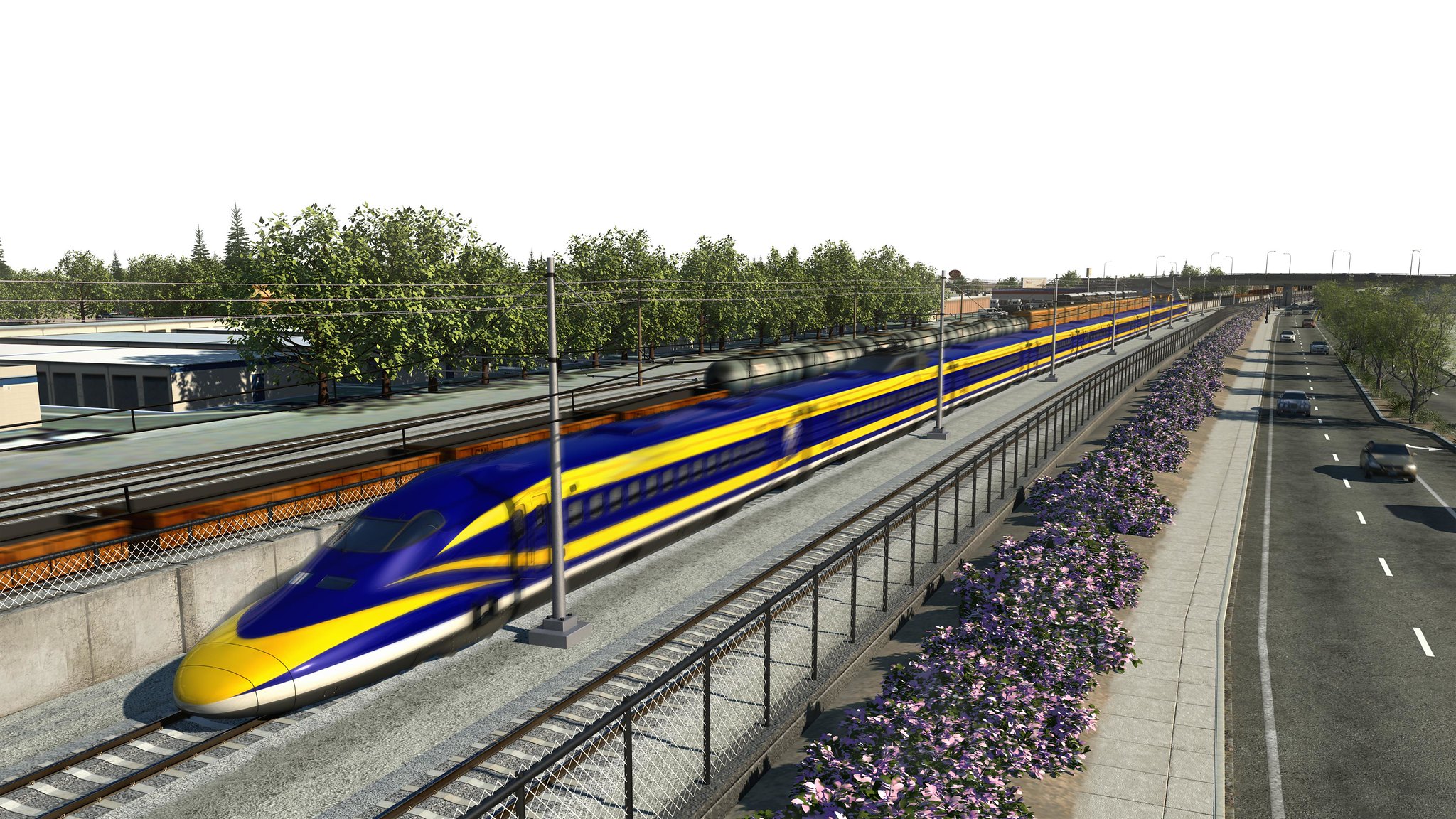

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s intentions were to continue with placing railroad tracks along Valley farmland and which would connect Bakersfield to Merced, but leading Democratic lawmakers erupted over the Central Valley link and worked to use the transit funds closer to their constituents in the state’s urban centers.

The California’s budget surplus of $97.5 billion gave the opportunity for the state to achieve both.

The surplus nearly sets in stone the 171-mile San Joaquin Valley rail project – having California residents to expect the long awaited bullet train to be finished around 2030.

The state funding for plans regarding the rail would also be increased to $3.65 billion this year resulting in finances being sent to projects such as Caltrain electrification and BART projects in the Bay Area to Downtown San Jose as well.

Another $4 billion is planned for transit infrastructure through 2025, although that money has yet to be allocated.

“We released the $4.2 billion, but we also got $3.65 billion in this year’s budget as a result of the compromise,” Rendon, the state’s foremost Democratic critic of the bullet train, said in an interview.

The independent inspector general’s office for this plan now holds tremendous powers to audit the High-Speed Rail Authority, where costs have skyrocketed over the recent years in the project.

Governor Newsom will hold the power to appoint the inspector general from a list comprised by the legislative committee.

“They know that with the inspector general that they’re going to be watched,” added Rendon. “They’re going to be held accountable.”

“Still, the squabble over high-speed rail during a record budget surplus does not bode well for the prospects of a bullet train whizzing from San Francisco to Los Angeles within the coming decades,” Ethan Elkind, director of the climate program at the UC Berkeley School of Law, said.

“It’s a once-in-a-generation amount of money that was just handed to the governor,” Elkind added. “And all (high-speed rail) has got is what they already had back in 2008.”

When the project was approved by voters in 2008, the expectation was a two-hour and 40-minute ride from Los Angeles to San Francisco, where it would connect to both Sacramento and San Diego costing a total of $45 billion. The cost of the project has nearly tripled reaching $113 billion with stops in Sacramento and San Diego having to be cut from the project.

There is not enough funding to construct the bullet train past the Central Valley which costs $23.8 billion. Even with bond money released in the latest budget, and revenue it receives from California’s cap-and-trade program, this portion may still require additional financial support to push it over the finish line due to drastic cost overruns and inflation.

Transit agencies around the state have been at the edge of their seats spectating talks in Sacramento due to the previous budget rerouting billions of dollars for other transit projects around the state to handle the bill for the high-speed rail.

Since lawmakers couldn’t secure an agreement with the governor, rail and bus operators were left out to dry without new money even with the major surplus of cash.

“It’s a very big deal,” said Rebecca Long, legislative manager for the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, an umbrella group that oversees transit funding in the Bay Area. “Last year that deal didn’t happen so the money basically evaporated,” she said.

Still, Long said Northern California transit did not get everything it wanted. The budget does not specify designated finances for Bay Area transit agencies, so BART, Caltrain, and the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority are all at a race to gain a portion of the budget for their projects that have been left underfunded. In Senate Leader Toni Atkin’s district, there has been roughly $300 million set aside for rail infrastructure which is located in the San Diego County.

“There’s no question that Southern California had some more leverage in this negotiation because more of the Southern California members were not comfortable with high-speed rail,” Long said.